The Frequency of Presence

Finding Our Natural Rhythm Through Physiology and Awareness

Living Above or Below Our Natural Rhythm

Presence isn’t some mystical ideal or spiritual performance, it’s a living rhythm within us. It has breath, pulse, and movement. When we’re attuned to our natural frequency, life feels softer: choices become clearer, creativity feels effortless, and our relationships begin to breathe again. It’s not about forcing ourselves to slow down or speed up, but about listening, learning the subtle music of our own being and letting that rhythm guide us home.

Imagine yourself as a radio, finely tuned to your own unique station. When you’re present, the signal comes through clearly, no static, no distortion, just a clean flow of energy and awareness. But when life pulls you off balance, the signal gets fuzzy. Too much noise, too much doing, and the music of who you are becomes harder to hear.

To find your true station, you don’t need to follow anyone else’s tempo or measure your worth by productivity. You only need to tune inward, to the quiet intelligence of your own rhythm. No one can find that frequency for you. It’s yours alone to rediscover.

And yet, it’s easy to lose that connection. Some days we move too fast, multitasking, rushing, pushed by demands and endless stimulation. Other days we feel slowed to a crawl, heavy, unmotivated, numb. In both cases, we drift away from what I call our presence frequency: that balanced physiological and energetic state where mind and body are synchronised with the now.

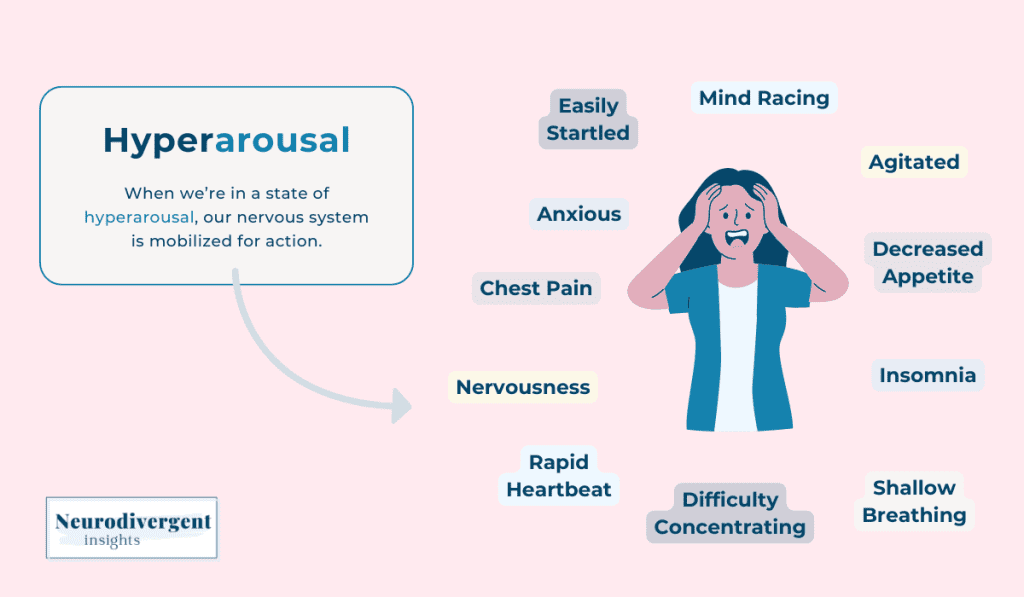

When we live above this frequency for too long, we enter hyperarousal, the “go faster” mode: racing thoughts, tension, anxiety, restless nights.

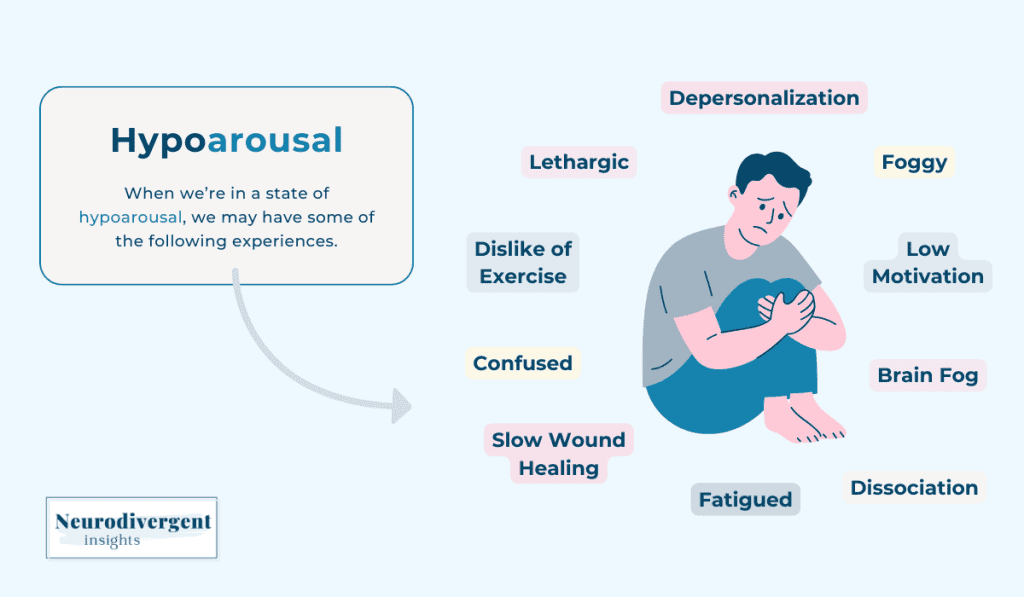

When we live below it, we fall into hypoarousal, disconnection, emptiness, fatigue, or depression.

Polyvagal Theory (Stephen Porges) 1994

These experiences reflect how our autonomic nervous system operates. The sympathetic branch mobilises energy, it’s the drive to act, to move, to protect. The parasympathetic branch restores energy, it invites rest, digestion, withdrawal, and recovery.

Health and presence aren’t about choosing one over the other, but learning how to dance between them. Our nervous system is meant to oscillate, to rise and fall, to act and rest, to connect and retreat.

According to Polyvagal Theory (Stephen Porges), this balance is guided by the vagus nerve, the bridge between body and mind that tells us whether we’re safe enough to open, connect, and feel at ease. When that rhythm is disrupted, our presence fragments, we stop feeling like ourselves.

Polyvagal theory helps us understand this beautifully:

Social Engagement (Ventral Vagal State): when we feel safe, open, and connected, we’re able to relate, express, and create.

Fight or Flight (Sympathetic State): when we sense danger, our system mobilises, heart racing, body ready to act.

Freeze or Shutdown (Dorsal Vagal State): when neither fight nor flight is possible, we withdraw, energy collapses, and we go numb. And perhaps most importantly, Co-Regulation reminds us that our nervous systems speak to each other. Safety is contagious. Presence is relational. When we are grounded, we help others find their rhythm too.

“Every inhale begins with an exhale — the rhythm of life itself.”

The Optimal State: Your Unique Natural Balance

Presence doesn’t mean sitting in perfect stillness or living without movement, it’s a dynamic balance, a living rhythm that’s entirely your own. In this state, your body feels awake but not tense, your mind alert but not racing. You’re relaxed without collapsing; centered, responsive, and gently attuned to both yourself and the world around you.

This is what I call your natural rhythm of presence. It’s the space where doing and being meet, where your breath flows easily, your thoughts slow down, and life feels less like a struggle and more like a conversation.

From a physiological perspective, this balance can be seen and measured. When we breathe slowly, around six breaths per minute, our heart-rate variability (HRV) increases, showing that the body is flexible and responsive rather than stuck in stress. The heart and brain begin to synchronise, creating a natural coherence that enhances focus, creativity, and emotional stability.

Even our brainwaves reflect this harmony. EEG studies show that when we are in this state, alpha waves rise, associated with calm, clear awareness, while the mental noise of overthinking begins to fade.

Yet this rhythm isn’t one-size-fits-all. Each of us has a slightly different “presence frequency,” shaped by our nervous system, our history, and the pace of our lives. Some people naturally move with a faster pulse, others a slower flow, both are valid. What matters is learning to recognise when you’re in tune with yourself and when you’ve drifted away.

A regulated nervous system oscillates. It moves fluidly between action and rest, expression and stillness. This gentle back-and-forth is what keeps us healthy, present, and alive.

When We Stay Out of Tune

When we drift too far from our natural rhythm for too long, something within us begins to fray. The body keeps trying to adapt, but eventually it pays the price. Living in constant over-arousal, always “on,” driven, alert, and doing, might look like strength from the outside, but inside it slowly erodes us. The nervous system never gets to exhale. Over time, this state can lead to burnout, anxiety, insomnia, hypertension, and even psychosomatic symptoms. The mind becomes scattered, the heart weary, and it gets harder to feel whole.

At the other end of the spectrum lies under-arousal, when life slows to a near standstill. Motivation fades, colours dull, and we begin to move through the days as if behind glass. This is the body’s way of protecting itself when the world has felt too much for too long. But in this protective stillness, we can also lose touch with our spark, with joy, curiosity, and the desire to engage with life.

Both extremes, too fast or too slow, are simply signs that our system is out of tune. Not broken, just out of rhythm. The pathways in the brain that support connection, play, and creativity start to quiet down when we’ve stretched past our capacity or collapsed beneath it. Presence isn’t a static state, it’s a rhythm that requires movement, flexibility, and care. Just like the breath, we need to expand and contract, to rise and fall, without getting stuck on either side. Learning to listen to this natural oscillation, and to return to it, is what keeps us connected, alive, and whole.

Age, Transitions, and the Art of Slowing Down

As we move through life, our natural rhythm changes. What once felt energising and effortless may begin to feel different. The pace that used to sustain us no longer fits the shape of who we are becoming. Yet our culture rarely honours this shift, it glorifies speed, productivity, and youth, while silence and slowness are often mistaken for decline.

As we age, the nervous system naturally seeks gentler cycles. The heart craves coherence over intensity; the breath wants depth rather than speed. This isn’t regression, it’s refinement. It’s the body’s way of aligning us with a deeper form of presence, one that values quality over quantity. Doing less, but doing it better. Each pause, each breath, each mindful moment becomes a gesture of care toward the person you are becoming. By slowing down, you’re not losing momentum, you’re reclaiming it. You’re allowing life to move through you rather than constantly running ahead of it.

When we learn to honour this natural slowing, we also cultivate a relationship with time itself, one that is kinder, more fluid, and deeply human.

Useful resources:

Using the Polyvagal Theory for Trauma | Dr. Stephen Porges

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CWVgXQKrqQ4&t=719s

Heart rate variability and slow-paced breathing: when coherence meets resonance

Breathing at a “resonant frequency” (~0.1 Hz ≈ 6 breaths/min) increases cardiac oscillations (HRV), improves stress management, and enhances executive functions. (PubMed)

How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing

Slow breathing (<10 breaths/min) increases HRV, improves EEG alpha activity, reduces anxiety and depression. (PubMed)

The Functions of Breathing and its Relationship to Breathing Therapy

Breathing within 4–6 breaths per minute synchronises cardiovascular and autonomic rhythms, supporting homeostasis. (breathwork-science.org)

Effect of Breathwork on Stress and Mental Health: A Meta-analysis

Paced breathing has measurable positive effects on stress and mental health via parasympathetic activation and HRV coherence. (breathwork-science.org)

Frequency of Positive States of Mind (Bränström et al.)

People who report frequent positive states show lower correlations between stress and depression; positive affect acts as a protective buffer. (BMC Psychology)